Check-out our Motorcycle Tours!

Intro

Basic premise: I am a BMW K models lover. I owned eleven BMW motorcycles: seven of them are K, including the current one; and only one GS, which was sold after a few months because I often preferred to ride my K1200GT. While I’m far from being a GS maniac, I have studied this bike series for a long time and have ridden many miles on all of its versions, from the R1150GS onwards, so I can speak knowledgeably about its strengths and weaknesses.

I continually meet proud GS owners and curious non-owners who bombard me with questions about the BMW GS, clearly the biggest motorcycle phenomenon of the last twenty years, so I was naturally drawn to investigate the reasons for this success.

I speak, of course, of the real GS—the R series 1200 or the 1250 in its standard or Adventure versions. There are other models, from the new F850GS down to the G310GS, but they are very different in layout and they don’t have the charisma of the most desired bike.

The real GS is a top seller, more than any other model, at least in Italy and other European countries, including little teen-ager bikes that cost a fifth, and its success only increases over time.

Those who have it are proud of it and tend to be loyal, but if they betray that loyalty, they often retrace their steps. Those who don’t have it think and talk about it often, sometimes just to criticize it:

- it costs too much

- it is ugly

- the shaft is hard and unbalances the ride

- with that suspension you cannot feel the front end.

More often, however, they wonder if maintenance is affordable, or if the seat is too high; but, above all, how can those who have it ride so fast. Because the GS is the Total Weapon, it is a magical object that transforms any toad biker into a Prince Charming.

In short, the GS is the bike that everyone must deal with, surrounded by its own special aura. Is this aura based on real facts? Or is it just marketing?

Some History

Long ago, serious motorcyclists were clearly divided into two categories: asphalt lovers and mud lovers; the former used to buy road motorcycles, possibly with a fairing; the latter, single-cylinder dirt bikes.

Things changed with the birth of enduros, a genre invented by Yamaha in the late ’70s with the XT500—bikes suitable for dirt roads and relatively challenging off-road tracks, but practical and comfortable enough to be used for long journeys on asphalt.

While the larger and more expensive touring bikes were not very common in the ‘80s, the more affordable single-cylinder enduros were very successful. During this decade the twin-cylinder BMW R80 G/S appeared, the progenitor of the modern adventure category. It seemed unnecessarily large and heavy then – even if seen today next to the R1250GS Adventure, it looks like its lifeboat – but it won several Paris-Dakar races, creating a solid reputation eating up Saharan tracks. For this and other reasons, it made his way into the hearts of fans.

A lot has happened since then. Initially, BMW was imitated by Honda (with its Africa Twin) and other makers. In recent years, however, adventure motorcycles and crossovers (two largely overlapping categories, the second designed more specifically for road use) have supplanted the super-sport and naked bikes in the hearts of motorcyclists. In this new era, the GS is the undisputed queen.

Today most bikers choose a GS or another adventure bike or a crossover, even if they seldom travel and the only dirt road they will see is the driveway of a bed & breakfast in Tuscany. It’s remarkable that the top seller among the classic, old-fashioned tourers, the BMW R1250RT, sells at the rate of only one for every 14 (fourteen) GS bikes sold.

How can this result be explained?

Reasons for Success

Marketing & Communication

First of all, behind the GS success, there is a hell of a lot of marketing. BMW mainly sells cars and cleverly exploits the ego of their buyers, convincing them that the GS is perfect for the Successful Man, and that it is so safe and easy to drive that anyone can ride it as a first bike.

BMW has also been the first in Europe to utilize balloon loans to allow many people to bring home a motorcycle that they could not otherwise afford.

Another strength is communication. Every single GS advertisement promises the freedom to go anywhere. Many GS buyers use it for commuting and little else, but they buy what really matters—the Dream of Absolute Freedom. This bike explicitly promised to be unstoppable, and even when, years ago, most GS owners were left on foot due to a stupid electronic problem, the message remained fixed in their hearts.

Design

The GS is certainly not the most elegant motorcycle in the world, but it is solid, well made, and has a masculine, robust, professional look with few frills. It looks like a Bosch tool, and it’s no coincidence that its cases resemble those of drills. The GS transmits competence and promises to extend this quality to its riders.

Technique

BMW was the first motorcycle manufacturer to fit its motorcycles with accessories, often of clear automotive derivation, to make them easier, more comfortable, safer, and more appealing. First came the ABS. It was proposed in the BMW K100 way back in 1988 (a fact that boosts my K lover pride), soon became the favorite accessory of the German brand customers and in 2012 it became a standard feature on all its models, way before any other maker.

Then came the traction control, the heated grips, the electro-assisted gearshift also in downshift, the automatic speed control, and dozens of other accessories that can raise the price of a bike by thousands of dollars.

The GS is also a concentration of unconventional technical choices which, as a whole, make the riding experience quite different from any other bike:

- integral braking system

- boxer engine

- shaft drive

- Paralever rear suspension

- Telelever front suspension.

Let’s see them in detail.

1) Integral Braking System

This has been offered standard or optional on the BMW R and K since the early 2000s. With it, the handlebar lever simultaneously activates both brakes, and the pedal can activate only the rear brake. It is therefore impossible to operate the front brake only, which creates a series of interesting advantages:

- simplifies the braking via a single command that perfectly balances front and rear braking, like on cars;

- eliminates the self-righting effect typically induced when using the front brake alone while cornering;

- helps to reduce nosediving while braking[1].

All this without precluding use of just the rear brake, needed in certain maneuvers such as U-turns, hairpin bends, and recovering from running too wide while turning.

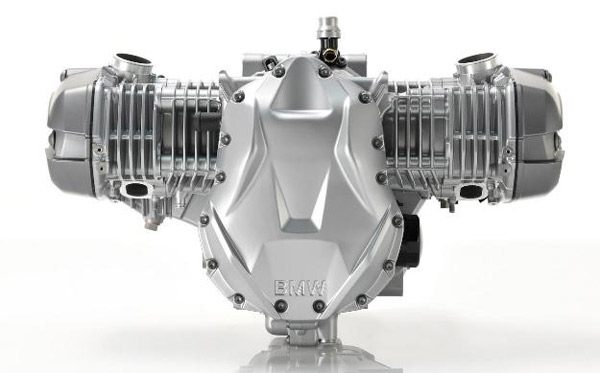

2) Boxer Engine

BMW bikes have always been distinctive from others because of the large twin-cylinder heads protruding from their sides, present only in some Eastern European models born as clones of BMW Wehrmacht sidecars. The production of K models began in the early 1980s, but, even today, many BMW customers still snub them, and consider their inline 3- and 4-cylinder engines essentially a mistake.

Before listing the real strengths of the boxer, let’s start by debunking an imaginary quality: the legendary low center of gravity. In today’s BMW, it simply does not exist.

Years ago, this kind of engine was mounted closer to the ground and actually helped to lower the center of gravity compared to other solutions. The increase in displacement and, therefore, the already considerable width of this architecture, coupled with the greater leaning angles enabled by modern tires, have imposed a much higher mounting, raising the center of gravity to a level comparable to other engine layouts.

Apart from this, the boxer engine offers some interesting advantages.

First, it transmits much less heat because the heads are relatively far from the rider and are perfectly exposed to dynamic ventilation.

Above all, the architecture with opposed cylinders guarantees, among the two-cylinders, the maximum regularity of rotation, particularly at low rpm, a traditional flaw of the twins. Any two-cylinder V-engine under 3000 rpm kicks, while the BMW boxer remains smooth below 2000 rpm in any gear even with full throttle, thus allowing the rider not to worry about the gear engaged: a great advantage, especially for beginners and relaxed riders.

The boxer layout also has some flaws. In addition to the engine width cited above, the torque reaction induced by the longitudinal crankshaft should be mentioned. An increase in rpms pulls the bike to the right side, typically by twisting the throttle at idle. Since 2004, this problem has been greatly reduced on BMWs, inserting a countershaft under the crankshaft; and virtually eliminated since 2013 with the new water-cooled boxer, where different transmission components rotate in the opposite direction of the crankshaft.

Incidentally, as a BMW K lover, I have to point out that the same problem of torque reaction should have affected even the 3- and 4-cylinder in-line engines of the K series, that also have the longitudinal crankshaft, but it was overcome brilliantly from the start by mounting the flywheel on the primary transmission shaft—and all that in 1983.

3) Shaft Drive

Many touring bikes are equipped with a shaft drive; but, among the adventure motorcycles and crossovers, it is rare. Other than on the GS, it is found only on the Yamaha Super Ténéré and the Honda Crosstourer.

The shaft has the great advantage of eliminating the need to clean and lubricate the chain every 500-1000 km, not a problem for motorcyclists accustomed to this practice, but a considerable hassle for those coming from cars or scooters and, in general, for those who travel long distances.

4) Paralever Rear Suspension

In the past, shaft drives caused the rear suspension to extend in acceleration and to compress while braking, a behavior that makes the ride awkward. BMW solved this problem by adding a second wishbone to the suspension and a universal joint between the shaft and the final bevel gear where there used to be only one on the gearbox side. Thanks to these devices and well-designed flexible couplings, the shaft transmission behaves practically like a chain – even simulating the chain pull! – the only real difference being the greater silence. Whoever says the opposite surely has never driven a modern shaft-equipped bike.

5) Telelever Front Suspension

Esistono altre moto con il motore boxer o con la trasmissione ad albero e la sospensione posteriore a quadrilatero, ma nessuna moto diversa da una BMW R o K ha la sospensione anteriore Telelever[2].

Other bikes are equipped with a boxer engine or a shaft drive with double swingarm rear suspension, but no bike other than a BMW R or K features the Telelever front suspension which, as is well-known, drastically reduces nosediving while braking[1]. This effect is not achieved by dumping the front shock absorber and thereby worsening the bump absorption (as happened on some Japanese motorcycles of the past), but by means of a peculiar geometry of the suspension which prevents the shortening of the wheelbase while braking. This fact allows the suspension compression over bumps while minimizing the compression due to weight transfer toward the front wheel.

This makes it possible to use an extremely soft shock absorber, very effective on hard bumps, while avoiding the excessive fork compression that would occur with a standard fork during hard brakings.

The advantages of this feature are considerable:

- the suspension perfectly absorbs the bumps, transmitting minimal stress to the handlebar;

- the bike keeps a substantially flat attitude while braking, even squeezing the lever, and this allows:

- to go into corners while braking quite hard without problems;

- to use the front brake even in a clumsy way, and even while cornering, without negative repercussions;

- a very efficient and mentally less demanding drive;

- unparalleled riding comfort for rider and passenger, and much less prone to jolts and attitude changes even in sporty driving;

- the avoided reduction of the wheelbase while braking that was mentioned above notably increases the stability of the bike during killer brakings;

- it is possible to apply the braking force on the front wheel almost instantaneously, rather than wait for the complete compression of the suspension, which results in a drastic reduction in the risk of panic-stop locks (currently avoided by the ABS).

Telelever detractors claim that it would prevent the driver from feeling the front wheel while braking, particularly in sporty driving. Well, after a lifetime of tests and comparisons, I can definitely say that this is nonsense. The proof is that those who drive a GS tend to go faster than with other bikes, which means that the bike gives them better performance and, thus, more confidence. This suspension is simply different; and, like all different things, it requires you to review your beliefs, an exercise that is not easy for some.

I detrattori del Telelever affermano che esso impedirebbe di percepire il comportamento della ruota anteriore, particolarmente nella guida sportiva. Beh, dopo una vita di prove e comparazioni, posso serenamente affermare che questa è una fesseria. Prova ne sia il fatto che chi guida un GS tende ad andare più veloce che con altre moto, il che vuol dire che la moto gli dà più confidenza. Questa sospensione è semplicemente diversa, e come tutte le cose diverse, richiede di rivedere le proprie convinzioni, esercizio non facile per alcuni.

Conclusion

In short, all these features contribute to making the GS a bike that is easy to buy and maintain, comfortable to ride, and easy to drive—so much so that it is really foolproof. Relatively limited driving skills are enough to make it go fast and with a noticeably reduced mental commitment. That’s why those who try it usually fall in love with it.

In short, if you have a GS, the real one, you have made a good purchase.

If you don’t have it, what are you waiting for?

Check-out our Motorcycle Tours!

[1] Actually, In the case of GS this effect is less important than on other bikes, as the Telelever suspension, which will be discussed later, provides right this effect, among other things..

[2] There is a different design with very similar effects: the Hossack quadrilateral suspension (Duolever) that equips the recent BMW K models (1200, 1300, and 1600) and the new Honda Gold Wing.